When a former spouse or partner dies, what would you feel? It depends on what your relationship morphed into or didn’t. For me, it’s just weird. It’s disenfranchised grief. Thoughts and a remembrance

Originally published in Mindful Soul Center magazine’s substack on 16 October 2022

It took eight days to remember that the third anniversary of a significant project had its annual moment. A missed opportunity to celebrate and share, and even promote what I consider an achievement, the publication of this magazine in print and in digital forms. There wasn’t a celebration or posts on social media. Sharing something on social media can seem trivial when dealing with big life situations. But it’s not trivial. My work, this creation, is meaningful and my contribution to the world. My blood, sweat and tears have poured into it. But, all of that took a backseat to a sad situation. I guess you can call it a ‘situation’.

That situation is the death of a man with whom I spent my young adult life, my former husband and partner for nearly 22 years. We existed together for 37% of my time spent on the planet. Yet, I haven’t existed in his world for the last 17 years. His death, such a big matter, has been nearly nullified by expectations and the quietude of myself and others. It’s weird. It’s also strange that because we’re not married anymore, it is socially acceptable to keep that grief quiet and even hidden.

How does his death impact my life right now? Technically in the material realm, it doesn’t. After all, we divorced and separated all the finances and bullshit in 2005. But it does matter to me. It’s an uneasy feeling not to feel comfortable sharing my sorrow publicly in the age of social media.

In 2022, we share our lives publicly when we want to feel supported and loved. That’s what we do now. For many people, that is part of our grief rituals now. People who lose a former spouse or partner experience disenfranchised grief.

It’s not about me anyway. Still, grief is for the people left behind. Not that I want more of it in my life. Who does? Right? Even so, I have the right to grieve the loss of my former husband, even if it isn’t socially acceptable to share it publicly.

The problem with death culture in the West is that it isn’t conducive to healing. It’s hidden, rushed, pushed aside and denied because people think death is contagious. Death is part of life. It is not separate from it. I’m sorry – not sorry – to break the news to you, but we’re all going to die. Here’s the headline:

Everyone you know and have loved – human and non-human – will die.

Get over it! I don’t mean for you to get over the grief. No, don’t rush your grief. I mean, death is a fact. Death is a part of life.

Grief

Was it my good fortune that I had the opportunity to grieve the loss of Mark through our divorce those seventeen years ago? Maybe. Probably. That grief was crippling then, and over time, it passed.

Grief was something that came to define us in some ways. We shared a lot of grief throughout our lives together. Not the typical grief around losing a parent or other family member. Our grief was a living grief that consumed us when a cardiac arrest and five-minute death shattered the world we had worked so hard to build together. That happened eight and one-half years into the marriage, eleven and one-half into the relationship.

Before that, things were good, then not so good, then good again, both challenging and promising – not great, but we were young and free and building a life together. Love changes and grows and becomes different things. We cared deeply about one another even when we fluctuated between the various kinds of love. That is until we passed the seven-year mark, frequently referred to as the seven-year itch. Seven years, that was the moment when things started to really come together. We nearly had a couple of years of great.

Maybe I’m romanticizing the eighteen months before the cardiac arrest. But in my memory, I was joyful and content. Life was just beginning at 30.

I spent a lot of time in my younger years not knowing exactly what I wanted, and now things were working out for me – for us. Our work hours were conducive to a healthy marriage, allowing us time for our personal interests and work, and weekends were spent joyfully together on joint interests.

I had an excellent job in the design department of a micro-woven textile company after finally graduating from university a couple of years earlier. We even had summer hours with half-day Fridays. My long mornings before work were filled with exercising and grooming horses twice weekly, art making and errands, and during the summer, weekly early morning trips to the beach without traffic.

After years of struggle and hard work, Mark’s business turned around. He was enjoying work, designing and renovating homes. Before that happened, at one point, he had to take on a second job unloading trucks on the night shift. He enjoyed gardening, playing on the computer, relaxing after work, cooking, unwinding and watching Seinfeld or puttering in his workshop.

Things were really working out. An idyllic life, peaceful times. That was the time I remember most.

Then at the ripe old age of 32, the other shoe dropped, as they say. I’m trying to get past that, but every time happiness seems to come near, even all these years later, it’s challenging to embrace it. One of my biggest struggles is always waiting for the other shoe to drop. It stems from the subtle forces of PTSD from the event that lingers below the surface.

He recovered. Things were good again, and then they went flat. Our marriage went from good to great to good to bad to ultimately the worst in the end. I don’t mean in the romantic sense, but in practicality, IRL!

Twenty-two years is not nothing – a double negative to make a point. In the early years of separation after the divorce that I initiated, I thought he would snap out of it and metaphorically wake up. But that never happened, and even though I gave up that hope so long ago, now it would never happen. It can never happen. Probably good that it didn’t. Still, I will miss him.

There have been very few times in my life when I absolutely required extra love and support from my friends, and this time is one of them. But it is also a time when there has been less understanding of my needs because it’s a weird situation that not everyone can relate to. There are a lot of former partners who will have a different experience of grief when their former spouse dies. Some former partners will not experience distress at all, and some might even be joyful. No judgement, but I’m not one of them. There really isn’t anything in place to allow me to share my grief due to the nature of my relationship with Mark – former spouse.

Even in the case of a normal situation, the truth is that a lot of people don’t even know that he died. Because I didn’t tell them. Plus, a lot of people don’t know how to behave when they encounter someone who has experienced a meaningful loss. We’ve forgotten as a culture that death is a part of life.

Everyone likes to talk about trauma and mental health these days to normalize it. Yet, so much of the sorrow and ensuing grief can be healed when a culture embraces and acknowledges that death is a part of life. Mostly, people medicate. That can sound judgy. But it is an actual fact, and I don’t care. Because, unlike Mark, who accepted everyone as they were, I’m not him. There is a severe abuse of pharmaceuticals in Western culture, especially in the US. To put a band-aid on the wound instead of addressing the cause of problems won’t cure the illness. It’s not all just brain chemistry. Anguish can turn into long-term suffering because we have abandoned, done away with or minimized death rituals.

Rituals and ceremonies

Rituals and ceremonies were how we healed and stopped despair from turning into long-term suffering. Obituaries are important to remember a life too. All of them are the tools we use to heal our hearts, even when the healing is a long process. I’m not one for lengthy wakes or embalming, personally. Cremation is perfectly fine for disposing of a body. Although, I think viewing a dead body can help immediate family members come to terms with the fact that someone significant to them has died. Going to a gravesite or mausoleum is a nice way to say goodbye. Or scattering ashes and having a memorial can be very healing.

If Mark had a viewing or memorial, it might seem inappropriate for me to attend or not? Who knows? I do know that there is an etiquette about this topic. But I’m far away, so it doesn’t really matter. Plus, Mark didn’t want a death ritual, and I don’t blame him for not wanting his body on display. Even so, it all seems weird to me. There wasn’t an obituary. At least I couldn’t find it. What the actual f—k? Sorry, not sorry again. He touched a lot of people’s lives and isn’t that the very least we can do to honour the dead?

I never wrote an obituary for anyone that played a significant part in my life, and every one should have one. I’m not going to follow all the rules. This is simply what I would write for a concise snapshot of his life. (I share many more memories later in the piece.)

Mark Alan Chasmar (obituary)

b. 24 September 1957, d. 29 September 2022

A designer and architect, Mark was a native of Hudson County. He was a dreamer and was loved by many. He grew up in Weehawken and graduated from Weehawken HS in 1975. Later he was awarded a degree in Architecture from the New York Institute of Technology. He loved architecture, design, art, music and culture. He renovated and built homes, and he liked to play the drums. He had a positive impact on a lot of people. He was funny.

He enjoyed baseball, and as a young adult, he coached little league with Frank Cemelli and brought the little buggers to the NJ State championship games. His friends were important to him, and his best friend, Steven Peletier, played a significant role in his life. Both of them survived life shattering events and both overcame them. Growing up on Duer Place in Weehawken, a few doors down from an incredible view of midtown Manhattan, he helped to stop the NYC skyline from being obliterated by high-rise apartments on Blvd East in Weehawken, even allowing his name to be on a lawsuit against Arthur Imperatore who was a land developer. He travelled by car across the country.

He was an entrepreneur running his own renovation and buidling firm, The Chasmar Corporation at one time. He worked for small architectural firms. He was a project manager for a an interior renovation of a large hotel in NYC. He worked at ABC News too. He was a good dancer. He spoke English and, although not fluent, spoke Spanish too and did a pretty good job of it when travelling.

He is survived by his partner Patricia McGough and her family, his brothers Mitchell and David Chasmar and their families, his cousin Susan Smyth who he considered a sister and her beautiful daughters Sarah and Jenna. Many other extended family members survive too. He genuinely wanted the best for his family and friends and truly loved them.

Times change and customs die too.

Things are changing, and now we’re allowed to embrace new ways of saying goodbye naturally. If he lived in a state where this was permitted or knew about this process, he might’ve chosen to return to the Earth through human composting. It’s legal in Washington state, Oregon and Colorado. Bills passed in California and Vermont, too, but there is a timeline before the law goes into effect in each state. Other states have introduced bills to allow this newer process to become legal and normalized. New comes as old ways die.

In 2008, I learnt about a custom from England and Wales when exploring Memento Mori as a topic for an interactive art project. The ritual was meant to help the dead in the afterlife, and it died along with the last known person to occupy the now unusual job of a sin-eater. One of the tasks of the sin-eater was to save the dead from walking the Earth as ghosts.

A sin-eater travelled around the country and attended the funeral rites of the recently deceased. The families would hire them to eat and drink food symbolically imbued with the dead’s transgressions, wrongs or other socially unacceptable behaviours – their sins. By eating food from a wooden platter that was either passed across the deceased’s body or placed upon it, they would assume the deceased’s sins. This act allowed the dead to bypass any judgement. The last known sin-eater Richard Munslow was buried in Ratlinghope in Shropshire, England, in 1906.

As the world and beliefs changed, so did this. Traditions die off, too; everything changes, but what are we replacing it with? We need more than the social media feed to soothe us.

Death is part of life, but it still hurts. 37% of a lifetime spent with someone just doesn’t disappear into the ethers or get recomposted into the Earth. Maybe, for some, the memories fade away, but I have an excellent memory. That part of my life matters to me. The experience no longer defines me, but it shaped me.

A former partner’s ritual and ceremony

So my ritual and ceremony will be in two forms. One private and one public. The private one is on the 1st of November, the Day of the Dead (Ziua Mortilor). Although the city’s graveyard doesn’t include any of my relatives, it is open to everyone to walk through it and honour the dead. People decorate graves with candles and flowers and leave offerings of food. Sometimes as the day turns into night, the philharmonic performs Mozart’s requiem or other dirges. You can even find an abandoned grave of someone that no longer has visitors or caretakers and decorate it. Usually, I celebrate the lives of the dead by visiting the graveyard in the early evening to experience the beauty of this celebration of life through death and not decorating a stranger’s grave. Instead, during the day, I place flowers on my balcony and burn a candle for each of my deceased relatives.

My public ceremony is sharing this piece to remember him and talk about a subject people don’t like to think about. Here I get to share some ways we celebrated life in the past and some defining moments that mattered to me – the good ones. That’s my way of coping. It is hard to know he isn’t here anymore, but it’s different for me. I did grieve all those years ago.

I’ll start with a disclaimer since, believe me, there were many times that I wanted to shake him or was highly frustrated. But I’ll spare you the drama because that’s mine, and I’ve healed over time.

Memories

In the earliest years of our marriage, when we felt like things were too complicated, and discord hit us – just as we were walking out the door to go to work – angry with one another, we both decided to call in and stay home to work it out. Our marriage – our relationship was more important than anything.

As I wept, Mark buried Macduff in the pouring rain, his grandmother’s cat who adopted us after she died. This was whilst Dominoe, the dog, sucked down MacDuff’s leftover kibble from his bowl. Thanks, Dommie, for the comic relief.

Before Gram died, we lived in the 2nd-floor apartment, and she lived on the 1st-floor. Mark treated her with so much love and respect. That is one of the things that attracted me to him. He cared so deeply for his grandmother. He also cared deeply for my mother and went out of his way to do things for her to help her out.

At the drop of a hat, he went with me to move my sister out of her apartment and to my mother’s when she was going through an extremely challenging time. He was an excellent brother-in-law to her and to Keith, our brother-in-law.

We created a home together and gardened together, growing a plethora of tomatoes and tomatillos, eggplant and jalapeño peppers, basil, cilantro, so many flowers and plants and, of course, catnip for Leusha and Tasmania, our kitty cats. He tended to the roses and pruned the grapevine.

We celebrated the arts by listening to the music of every genre, from Ravi Shankar and Hindi movie music to George Michael, Miles Davis, Stephen Stills and Stevie Wonder. We sometimes blasted classical music and danced like we were listening to rock and roll. We looked ridiculous, and the opposing forces of our spasmodic dances set against Beethoven, Bach and others were riotously funny to both of us. We laughed so hard, we cried.

We participated in the arts by taking turns drawing silly pictures rapidly on the easel as we blasted more music.

We played games regularly, chess sometimes but mostly backgammon. We played on the computer and the internet learning new software programs and reading Osho’s Zen tarot cards in the early days of the internet.

Elisa and other co-workers organized a bridal shower for me back in 1986. One of the gifts we received, probably the only practical gift since there was a lot of lingerie, was a gift certificate to Fortunoff’s. Mark declared that it must be used to purchase a high-quality stainless steel tomato strainer and a giant pot to make the gravy, so we did. In the freezer, we kept ‘units’ in quart and pint-sized containers left over from our Chinese take-out. We never ran out.

We cooked, boiled, baked and sautéed together. Our staples included a daily batch of Florence’s classic Red Rose Iced Tea with sugar and lemon and Uncle Gary’s famous tomato sauce, aka ‘the gravy,’ both cherished recipes. When we lived in the same house as Mr Mimo, Mark’s brother, there were the sauce wars. Oh, the spoils of war! I was always well-fed as each competed to make the best sauce. No one ever went hungry in our home, wherever it was at the time.

Christmas was our big holiday. We hosted around 30 people every year for dinner. We started the celebration in the evening, not at our house but at Uncle Gary’s. Eating a traditional Italian Christmas Eve dinner with salted cod fish and broccoli with lemon and garlic. Susan would wrap presents for the girls, and then we would be on our way. This was our fuel since on our way home, just after midnight, we absconded a Christmas tree from the local DQ lot. We stayed up all night preparing the feast and decorating the tree. We were only to sleep for a few hours before our guests arrived. There were gifts for everyone, even unexpected guests. It was a tradition.

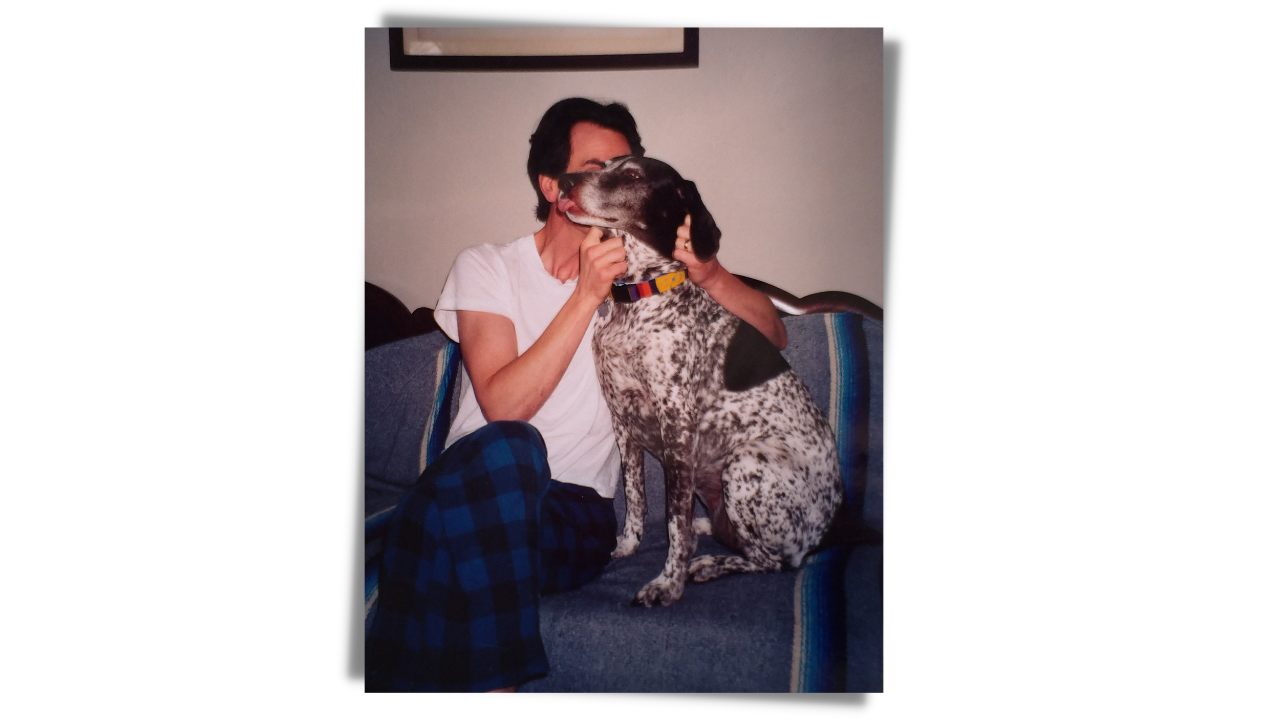

He was full of surprises. One day, he asked me to run an errand with him to pick up a sign for his business. We pulled up to a house that had the ugliest sign you could imagine posted out front. I waited in the car, hoping that the signmaker had created something very different. A few minutes later, Mark opened the car door and placed a German shorthair puppy in my lap. Surprise! That’s how Chelsea came to live with us.

One year earlier, I came home from work, and in the middle of the living room was a box with a note attached. It was an introductory note from Leusha and Tasmania, two kittens. That was a few months after MacDuff the cat died.

He helped so many people, but something more important is that he accepted everyone, warts and all. He didn’t judge people.

So there it is, some of my fondest memories with a kind soul that is now free from pain and a body that presented more challenges than most people will ever know in a lifetime. He had a wounded heart, a traumatic brain injury, and cancer multiplied times three. Still, he never wanted you to feel sorry for him. All of that was coupled with a strong desire to live, and he wasn’t afraid to go deep into the abyss to explore the shadow from time to time. But he doesn’t need to do a deep dive anymore. That’s what is required of the living.

You can read a few comments from people who knew Mark in the newsletter edition on Substack.